Historical Review: From Humble Bus Stop to Global Chokehold — How RTrans Became “TransFEMM” and Accidentally Misplaced Affordable Living

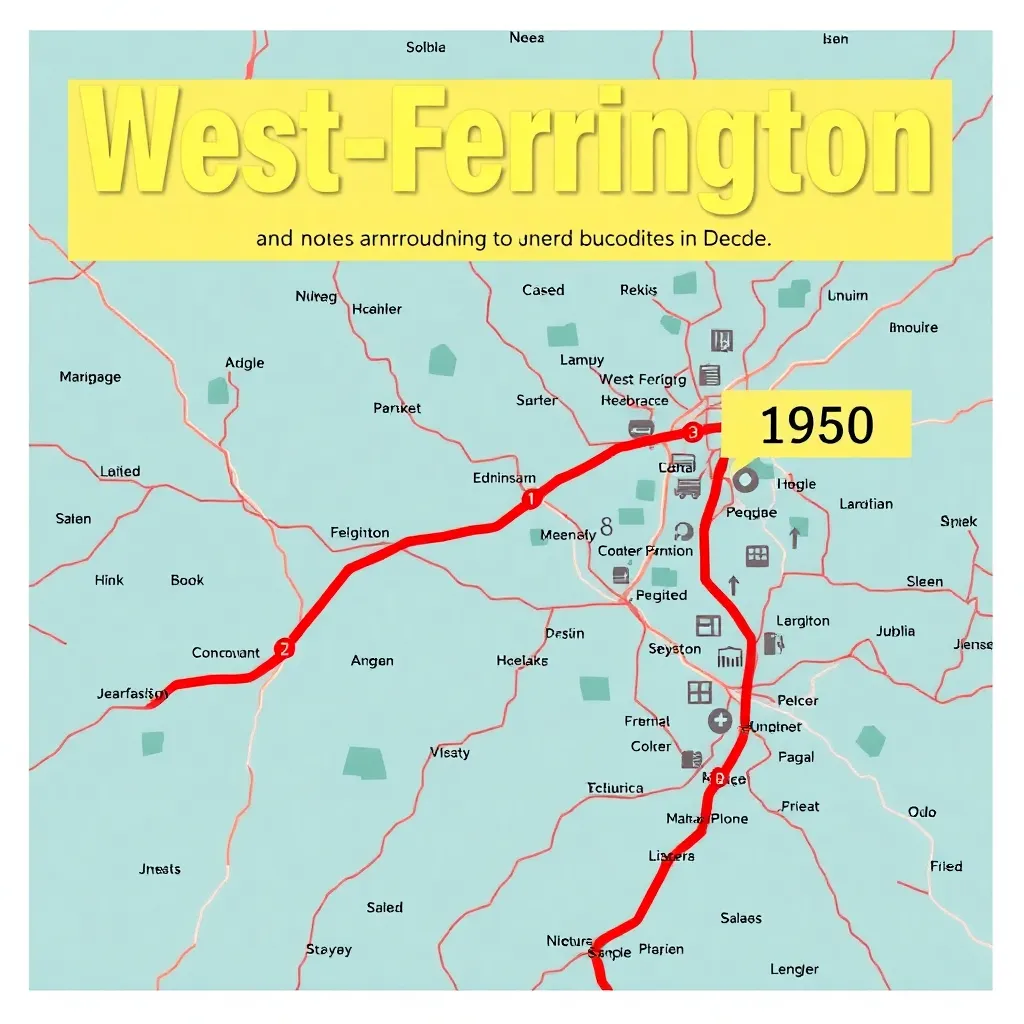

WEST-FERRINGTON, JAN. 1 — Every nation has a founding myth. Some have heroic uprisings. Others have sacred documents. Ours, apparently, began in 1950 with a man, a clipboard, and a bus timetable so optimistic it could qualify as political fiction.

According to recently re-celebrated local archives (and the collective trauma of anyone who has ever tried to send a parcel three towns over without taking out a small loan), the story starts on January 1st, 1950, when a modest transportation outfit calling itself “RTrans” opened its doors in the small town of West-Ferrington.

Its mission was simple: put buses on roads and stops on maps, and perhaps—if all went well—make the 7:40 a real thing rather than a spiritual concept.

It succeeded.

And then, as history repeatedly warns, it succeeded harder.

The Early Years (1950–1960): A Company That “Just Wanted to Help,” Like a Cat That “Just Wants to Sit on Your Keyboard”

RTrans’ first decade is remembered with the soft, sepia glow usually reserved for childhood summers and interest rates below the stratosphere.

In the early 1950s, the company:

bought new buses,

opened new stops,

expanded routes inside West-Ferrington,

and gained a reputation for being the rare organization that could operate vehicles and occasionally show up.

But the true turning point came when local authorities requested something bigger: routes linking the regional capital with surrounding towns and villages.

This is the part historians now identify as “the moment everyone applauded the beginning of their own future inconvenience.”

By 1960, RTrans had grown into a major regional bus network—large enough to matter, small enough to still pretend it was everyone’s friendly neighbor.

It was, in hindsight, the last time anyone described the company as “charming.”

The Golden Expansion (1960–2000): When the Government Looked at One Company and Said, “Yes, Let’s Do This Forever”

The 1960s saw the next leap: the government chose RTrans for nationwide transportation, a decision now remembered as either:

a bold modernization strategy, or

the administrative equivalent of giving one raccoon the keys to every trash can in the country.

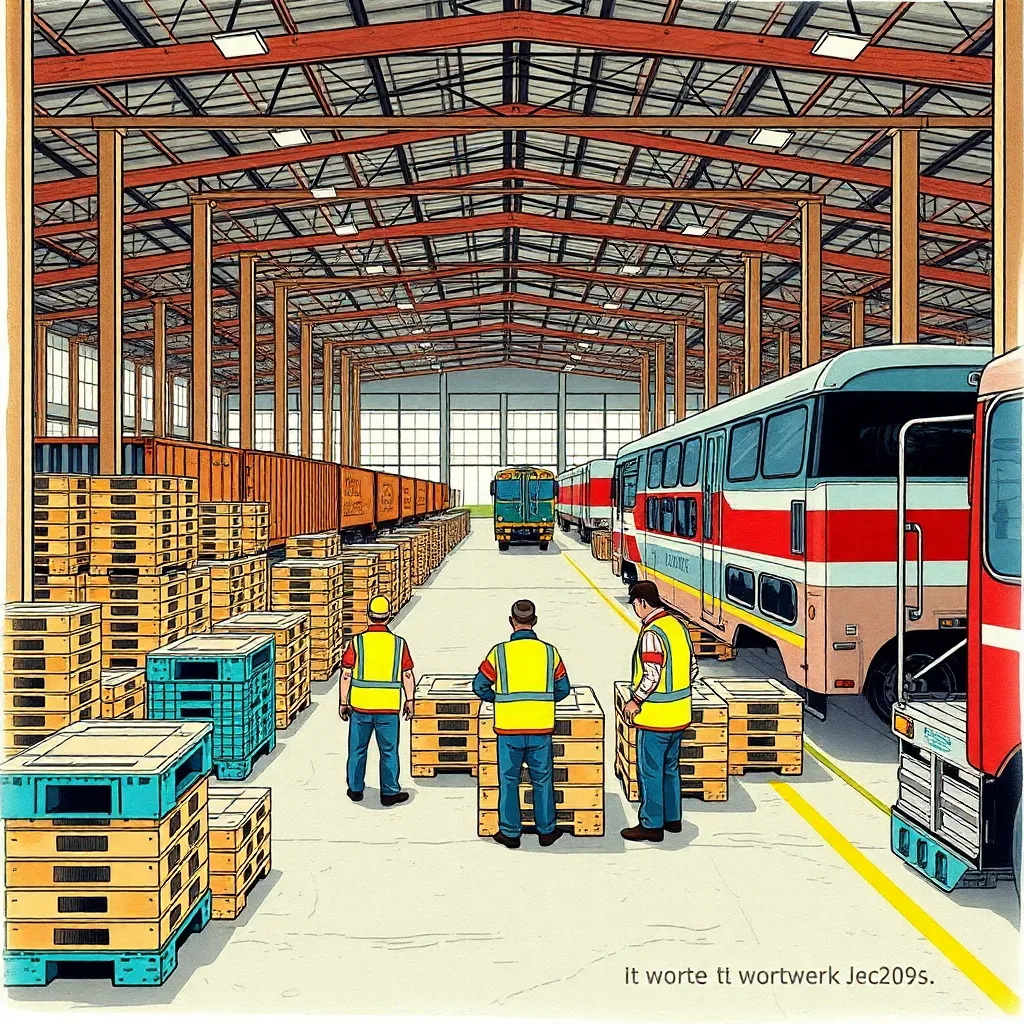

Initially, the partnership seemed brilliant. The government asked RTrans to build the first railway, connecting coal and iron mines with the rapidly expanding steel industries.

There were subsidies. There were ribbon cuttings. There were speeches about progress, delivered beside freshly laid tracks that still smelled faintly of national ambition.

For decades, the system worked:

RTrans grew quickly.

The country benefited from a more efficient network.

Everyone was too busy enjoying the novelty of goods arriving on time to ask, “Should we maybe not let one company become the circulatory system of modern life?”

By the late 20th century, RTrans wasn’t just a transportation provider; it was a national reflex. People didn’t plan journeys anymore. They planned around whatever RTrans decided was spiritually best for them.

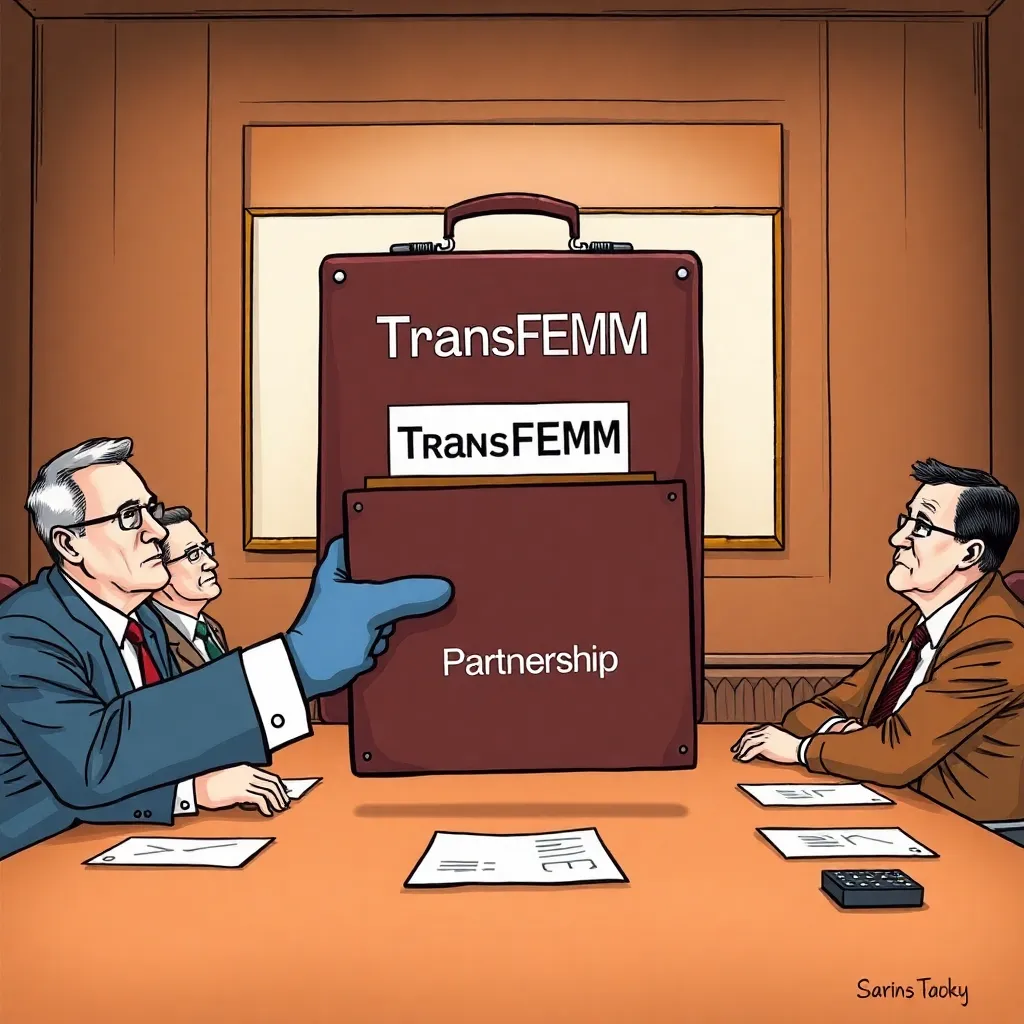

The Millennium Shift (2000): The Rebrand Heard Around the Wallet

Then came January 1st, 2000—exactly 50 years after RTrans’ founding—when the company decided it had outgrown being a national infrastructure partner and would now become something much more serious:

a global inevitability.

RTrans registered a new international name: “TransFEMM.”

It also installed a new CEO, an event which corporate historians describe as “leadership transition” and everyone else describes as “when the vibes permanently changed.”

TransFEMM’s expansion strategy was breathtaking in its simplicity:

Buy local transportation companies, along with their vehicles and infrastructure.

Build massive international superhighways and high-speed rail, preferably in ways that looked like public service but behaved like private leverage.

Become so embedded in global movement of goods and people that alternatives began to feel quaint, like writing letters by candlelight.

In many places, TransFEMM didn’t enter markets so much as it occupied them—with the polite smile of a firm that knows you need it more than it needs you.

The 2010 Benchmark: “Nearly 70% of Global Transportation,” or “What Could Possibly Go Wrong?”

By 2010, by the company’s own widely repeated narrative and by many observers’ increasingly tired calculations, nearly 70% of global transportation ran through a single corporate channel.

That is not merely market dominance.

That is planetary dependency with a logo.

And once TransFEMM recognized itself as a dependency, it began acting like one, in a sequence historians will someday call:

“The Predictable Part.”

Reports and public frustration began piling up around familiar themes:

Price increases, not explained so much as announced.

Small routes closed, especially those used by ordinary people rather than high-margin bulk transit.

Government lobbying and bribery allegations, which, depending on jurisdiction, are either called “corruption” or “stakeholder engagement.”

New infrastructure built at astonishing prices, inevitably described as “investment,” “nation-building,” and “unavoidable,” even when budgets began resembling science fiction.

In interviews, citizens began noting a strange new phenomenon: everything, everywhere, was becoming expensive—and somehow the cost always traced back to moving the thing.

Your groceries weren’t just pricier. Their journey had become a toll road in disguise.

The Modern Consequence: Why Your Cheap Stuff Isn’t Cheap, and Your Nearby City Is Now “Logistically Unavailable”

TransFEMM, critics argue, didn’t just raise prices. It reshaped the idea of access.

A growing list of complaints has become almost universal:

“Why is shipping more expensive than the product?”

“Why can I order something from across the ocean, but not get a train to the next city?”

“Why did the route that served three towns disappear overnight?”

“Why does every alternative company seem to collapse immediately, like a candle in a wind tunnel?”

In the popular telling, new competitors attempting to enter the transportation market are “instantly destroyed.” Whether by price wars, infrastructure denial, regulatory hurdles, or the simple fact that TransFEMM already owns the metaphorical roads—sometimes literally—many challengers don’t survive long enough to print business cards.

Governments, meanwhile, are described as unable to act, because they have boxed themselves into a single option: TransFEMM.

When one company owns:

the vehicles,

the routes,

the rails,

the highways,

the logistics contracts,

and a suspicious amount of “public-private partnerships,”

then “choosing someone else” becomes less a policy decision and more a fantasy genre.

A Timeline of the “Accidental Empire”

1950: RTrans founded in West-Ferrington to run a town bus network.

1950s: Adds buses and stops; local success turns into regional expansion.

1960: Large regional bus network established.

1960s–1990s: Government chooses RTrans for nationwide transportation; first railway links mines to steel industries; subsidies fuel growth; country benefits.

2000: RTrans becomes international, rebrands as TransFEMM, appoints new CEO.

2000–2010: Aggressive global acquisition of local transport firms; builds superhighways and high-speed rail.

2010: Reported dominance of global transportation reaches staggering levels.

2010–present: Prices rise, routes shrink, alternatives struggle, governments appear increasingly “consulted” rather than “in charge.”

The Official Explanation: “Costs Are Complex,” Says Company Whose Business Model Is Literally Moving Things

When confronted with the public’s growing rage, a representative corporate statement (typically delivered from a podium that cost more than a small hospital) tends to include several recurring phrases:

“unprecedented demand”

“global conditions”

“necessary modernization”

“supply chain challenges”

“strategic network optimization”

Translated into ordinary language, “strategic network optimization” means: we removed the services you relied on because they were inconvenient to our profit margins.

The Historical Lesson: Infrastructure Isn’t Just Concrete — It’s Power

Looking back, the arc from RTrans to TransFEMM reveals a simple truth historians have been trying to tattoo onto policymaker foreheads for centuries:

Whoever controls movement controls everything else.

It starts innocently enough—buses, stops, routes to nearby villages.

Then a government wants efficiency, and chooses a single trusted partner.

Then that partner becomes essential.

Then essential becomes untouchable.

Then untouchable becomes expensive.

Then expensive becomes normal.

And eventually, you wake up one day and realize you can’t afford a cheap table because the cost of delivering it has been politely inflated by the same company that also, coincidentally, determined there no longer needs to be a train to the next city because the next city wasn’t sufficiently profitable.

Closing Reflection: A Bus Company That Outgrew the Planet

In West-Ferrington, the original RTrans bus stop still exists, locals say—though the timetable is now mostly decorative, like a museum plaque commemorating an era when transportation was a service instead of a leverage point.

If the story of TransFEMM is a cautionary tale, it is not about technology, globalization, or even greed.

It is about what happens when a society hands the keys to its mobility—its trade, its commuting, its supply lines, its food prices, its access to opportunity—to a single entity and then acts surprised when that entity starts charging rent on reality.

Because once one company becomes the road, the rail, and the route, the rest of us aren’t customers anymore.

We’re cargo.