Wibble Investigates: The Three Kingdoms of Game Development (AAA, AA, and Indie), Ranked by How Much They Hate Your GPU

In an inspiring display of human ambition, modern game development has evolved into three distinct studio species—each perfectly adapted to its environment, like sharks, pigeons, and whatever lives at the bottom of a keyboard after six years of crumbs.

Industry analysts traditionally classify studios by budget, headcount, and scope. The Wibble, however, prefers more accurate metrics: how many national economies were liquidated during pre-production, whether the dev team shares a toothbrush, and what kind of computer you need to open the settings menu.

Below is a definitive comparison of AAA, AA, and Indie studios, based on rigorous research, several whispered confessions, and one person on Discord who said “trust me bro.”

Budget: Funding Models Ranging from “Absurd” to “Coffee-Adjacent”

AAA — One Infinity Dollars

AAA budgets are no longer measured in millions because numbers are limiting and executives hate limits. Instead, AAA projects are financed using one infinity dollars, a currency backed by pure optimism and the belief that whales will always exist.

This money is primarily spent on:

cinematic trailers that imply gameplay will happen someday,

licensing a celebrity face to stare sadly at the camera,

and creating a cloth simulation system so advanced it can model the emotional weight of debt.

AA — The Whole GDP of Nigeria

AA studios operate in the comfortable middle class of game development: not quite “infinite money,” but still enough cash to make accountants sweat through their shirts.

Their budget is often described as the whole GDP of Nigeria, which means:

marketing is “a trailer and hope,”

the studio can afford some motion capture,

and someone will definitely suggest adding a battle pass “just in case.”

Indie — One Cup of Coffee Worth of Cash

Indie studios are funded through a bold financial strategy known as “what’s left after rent.” The entire project may be backed by a single cup of coffee’s worth of cash, which the developer will not drink because it must also serve as the emergency fund.

Additional indie funding sources include:

“exposure,”

loose change found in couch cushions,

and an ancient Patreon supporter named “Greg” who never comments but always pays.

Development Team: From Megacities to Friend Groups That Share Trauma

AAA — The Entire Population of India

AAA teams are so large they have their own weather systems. When the entire population of India is working on your game, communication becomes a kind of interpretive dance performed across 47 departments and an ominous Slack channel titled “FINAL_FINAL_2.”

Key benefits of AAA staffing:

every pixel gets its own specialist,

meetings can achieve escape velocity,

no one knows who implemented the loot system but everyone is afraid to touch it.

AA — Twenty Random People Who Don’t Know Each Other

AA development teams are like a heist movie cast assembled by algorithm. Twenty random people who don’t know each other come together under one banner, united by a single shared belief: this might ship if we stop adding features.

They are typically:

talented,

overworked,

and bonded by the universal AA experience of “we can’t afford to redo this, so it’s a design choice now.”

Indie — A Queer Polyamorous Friend Group

Indie teams are frequently a queer polyamorous friend group who met during a jam, moved in together, and now communicate exclusively through inside jokes and a shared Trello board.

Strengths include:

quick decisions (usually made at 2 a.m.),

radical creativity,

and the ability to replace the entire combat system because someone had a dream about frogs.

Development Time: The Clock as a Suggestion, Not a Boundary

AAA — 100 Years So Far (Delayed Indefinitely)

AAA development time is measured in geological layers. The project has been in development for 100 years so far, delayed indefinitely, and will be “reimagined” three times before anyone admits it’s actually just the same game with different menus.

AAA schedules are built around:

the financial quarter,

the executive’s mood,

and whether the engine has learned to stop exploding.

AA — 5–10 Years

AA studios take the respectable approach: 5–10 years, which is long enough to build something substantial and short enough to still vaguely remember the original design document.

Common AA milestones:

Year 2: “We have a vertical slice!”

Year 6: “We are removing crafting.”

Year 9: “We are adding crafting back.”

Indie — Until It’s Ready

Indie development time is “until it’s ready,” which means:

the game is launched when it feels emotionally complete,

or when the developer is forced to eat ramen for the 800th consecutive day and decides release is preferable to death.

Game Engine: A Spectrum from “Real” to “Actually Works”

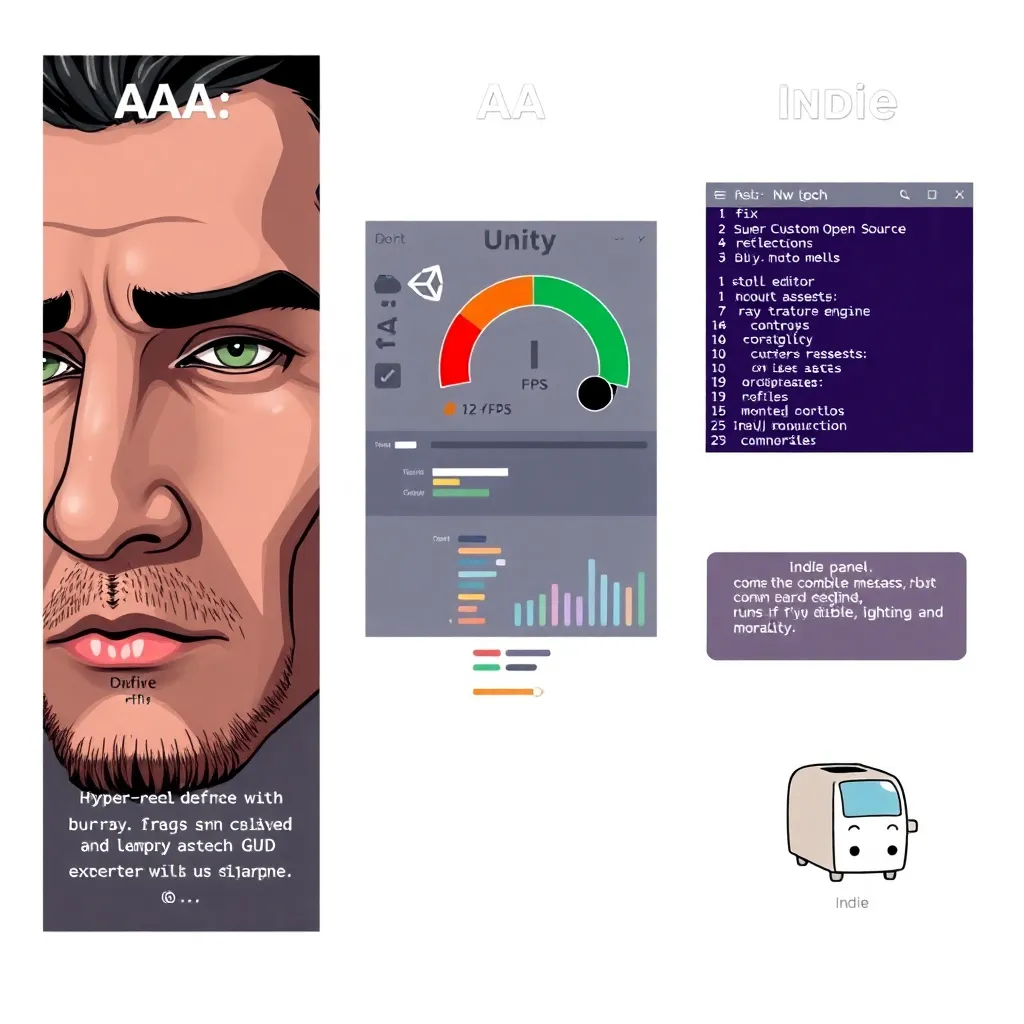

AAA — The REAL Engine (Cool Graphics, No Performance Whatsoever)

AAA studios often build their own tech: The REAL engine, which produces graphics so stunning they briefly convince you your PC has evolved—right before it melts into a cautionary tale.

The REAL engine excels at:

pores,

reflections,

and achieving 12 FPS while the main character opens a door.

AA — Unity

AA studios use Unity because it:

works,

is supported,

and comes with the added thrill of wondering whether the next update will quietly invalidate your entire pipeline.

Unity’s true superpower is letting a mid-sized team ship something competent without inventing “Texture Streaming 2: Streaming Harder.”

Indie — Super Custom Open Source Engine

Indie studios create super custom open source engines because:

they can,

they shouldn’t,

and they have strong opinions about how physics should feel.

The engine often has:

three contributors,

400 commits titled “fix stuff,”

and a feature list that includes “runs on a toaster if you disable lighting, sound, and morality.”

Hardware Requirements: From NASA to “Processor (Optional)”

AAA — NASA Supercomputer (Recommended for 1080p 60fps with 144p Upscaling and Frame Generation)

AAA games now list requirements like a threat.

To hit the recommended settings—1080p 60fps with 144p upscaling and frame generation—you need a NASA supercomputer, a small hydroelectric dam, and the willingness to forgive the game for stuttering during cutscenes.

The typical AAA experience:

gorgeous visuals,

unplayable performance,

and a “Day One Patch” the size of a minor religion.

AA — Decent Gaming PC

AA studios believe in reasonable expectations. A decent gaming PC will do. You might even get to play at native resolution, like our ancestors once did, before they were seduced by ray-traced puddles.

Indie — Processor (Optional)

Indie games are optimized through sheer humility. A processor is optional. Some titles run on:

integrated graphics,

ancient laptops,

or pure determination.

Performance is less “frames per second” and more “vibes per minute.”

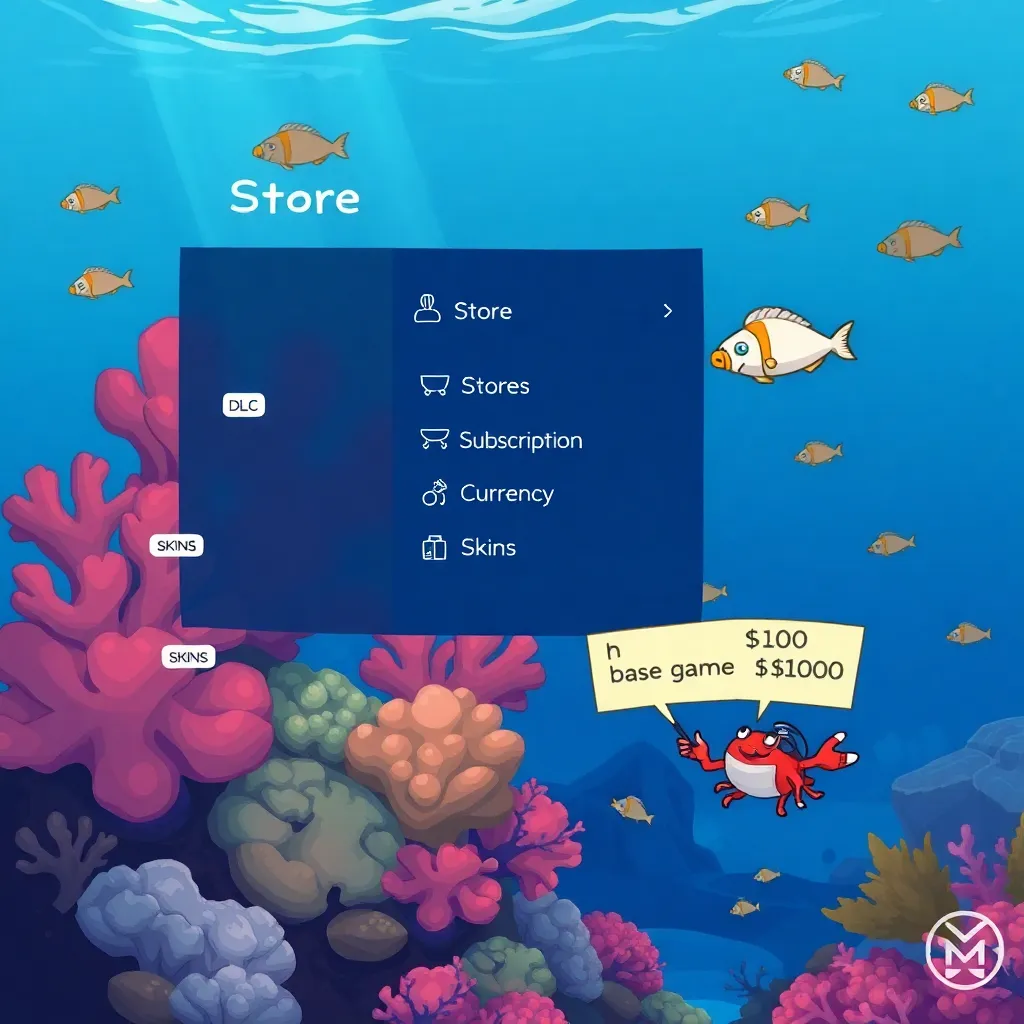

Monetisation: The Art of Charging You for Air

AAA — $100 Base Game + $120 DLC Starter Bundle + $29.99 Subscription + Paid Currency and Skins

AAA monetisation is an ecosystem. The game is merely the reef; the purchases are the fish; you are the plankton.

Your $100 base game includes:

a store,

a store tutorial,

and a story campaign that teaches you the true meaning of “engagement.”

Then comes the $120 DLC starter bundle, the $29.99 service subscription, and the paid in-game currency, which is always sold in amounts that make math inconvenient on purpose.

AA — $20–40 Full Game

AA studios sell you a game like it’s 2007. This approach is considered radical and possibly illegal in several boardrooms.

For $20–40, you receive:

the full product,

some updates,

and a quiet sense of peace.

Indie — “If You Like This Game, You Can Support Me Here.” GitHub Version Free.

Indie monetisation is:

gentle,

apologetic,

and often accompanied by a sentence like “no pressure.”

You can support the dev here. Or you can get the game for free from GitHub. Or you can fork it and accidentally become a co-maintainer for six months.

Sequels: Repetition, Patience, and the Concept of “Just Update It”

AAA — Same Exact Game Released Each Year for Full Price

AAA sequels are annual traditions, like holidays or taxes.

Each year’s installment features:

slightly different lighting,

a new menu layout,

and a weapon skin called “Obsidian Bloodfire” that costs $19.99.

AA — “After Many Years, the Long Awaited Sequel Finally Released”

AA sequels arrive with genuine excitement and the sense of time passing. They are announced with reverence: “after many years, the long awaited sequel finally released,” and fans rejoice because the studio didn’t vanish into the void.

Indie — “No Need for Sequels When Updates Add More Content Than AAA Puts in the Whole Game”

Indie devs simply keep updating the same game until it becomes a living artifact.

At some point, patch notes read like epic poetry:

“Added fishing.”

“Added existential dread mode.”

“Added 40 hours of new content because I felt like it.”

Modding: Crime, Feature, Identity

AAA — Instantly Banned for Having a NexusMods Account

AAA studios have boldly redefined modding as a form of extremism.

If you so much as think about NexusMods, you are instantly banned for having a NexusMods account—whether you do or not. It’s preemptive justice, driven by the fear that players might:

fix bugs,

improve UI,

or remove the store tab.

AA — Yes

AA studios allow modding because:

they understand it extends the game’s life,

and it makes the community do free work, which is the most sustainable business model ever invented.

Indie — This Game Is a Mod

For indie titles, modding isn’t supported—it’s the point. The entire game is a mod, spun out of another mod, inspired by a forum post from 2014, and held together by open source libraries and hope.

Community: Ghost Towns, Megacities, and Strange Little Villages

AAA — None

AAA communities are often described as “none,” because the player base has been fragmented into:

region-locked micro-communities,

monetisation tiers,

and people who only log in to complain about monetisation tiers.

Any attempt at community building is replaced with a “Season Roadmap” and a corporate tweet saying “We hear you.”

AA — The Most Popular Discord Community in the World

AA communities gather in Discord servers so large they could qualify as sovereign nations.

They have:

memes,

fan art,

balance debates,

and one moderator named “Kyle” who hasn’t slept since launch day.

Indie — A Random Independent Web Forum You’ve Never Heard Of

Indie communities live in mysterious web forums that look like they were last updated during the reign of Netscape.

Somewhere, deep in the internet, 38 people are intensely discussing:

whether the new stamina curve is “philosophically consistent,”

and how to compile the nightly build on a refrigerator.

Conclusion: Choose Your Fighter (and Your Financial Future)

AAA studios deliver spectacle, ambition, and a shopping cart disguised as a menu.

AA studios deliver solid, approachable games with real communities and reasonable hardware demands.

Indie studios deliver weird brilliance, open-source chaos, and patch notes that sound like diary entries.

In the end, each model has its place in the ecosystem—much like volcanoes, suburban malls, and that one guy selling handcrafted roguelikes from a trench coat on GitHub.

And whatever you choose, remember the golden rule of modern gaming:

If it runs well on your machine, it’s probably indie.