Groundbreaking Study Finds Pyramids Were “Reverse-Built” From Solid Rock, Explaining Why Egypt Has So Much Desert

CAIRO—In a discovery already being described by experts as “either the biggest leap forward in archaeology or the most ambitious attempt to avoid admitting anyone ever carried anything heavy,” a new study claims the Egyptian pyramids were not built block by block at all, but instead carved directly out of bedrock—while the leftover stone was painstakingly ground down into desert sand.

The research, published in the prestigious journal Annals of Things We Would Have Noticed Sooner If True, proposes that ancient Egyptians approached monumental architecture the same way a modern office approaches a birthday cake: by removing everything that isn’t the final shape and leaving crumbs everywhere.

“People have always asked where the stones came from,” said lead author Dr. Leila El-Mostafa, gesturing broadly at the Sahara. “Now we can finally answer: they came from the pyramids, and then they became… this.”

“Construction” Rebranded as “De-Construction, But Backwards”

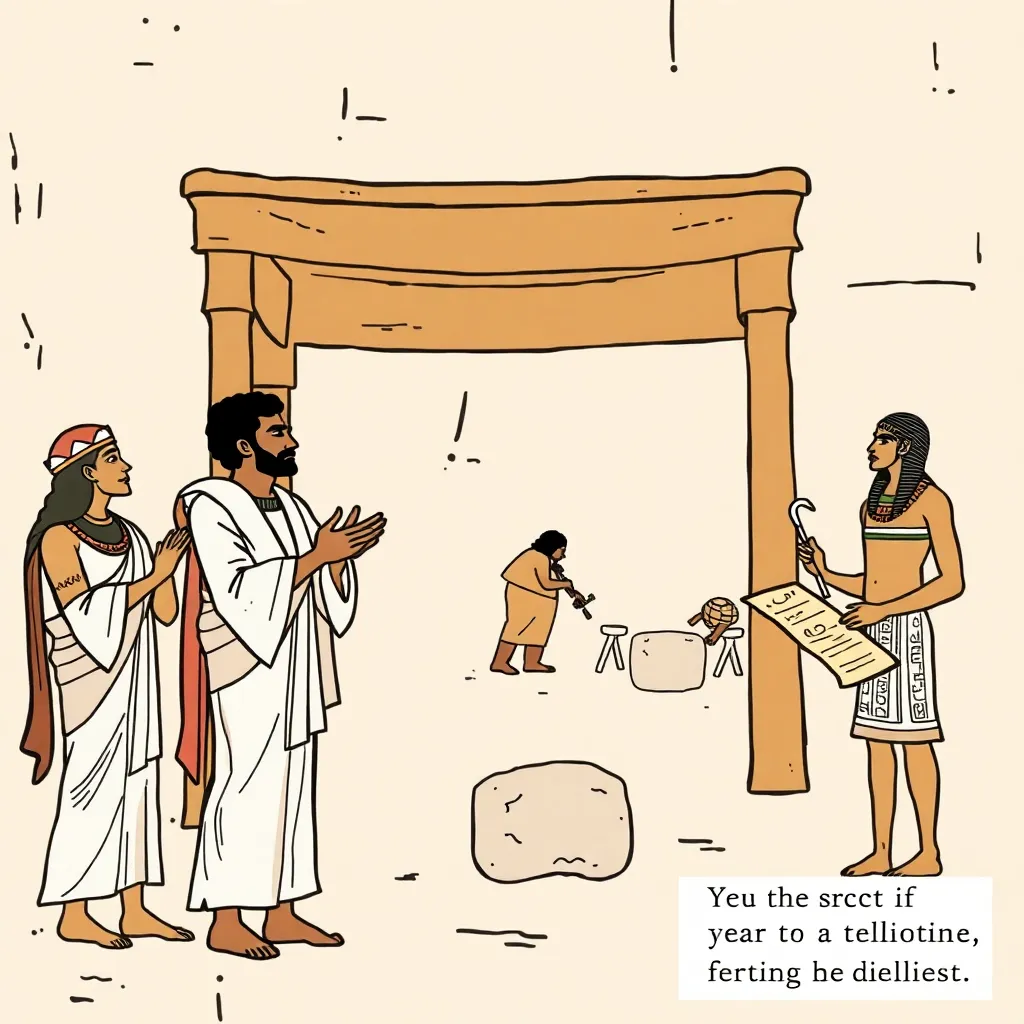

For centuries, students, tourists, and documentary narrators with unusually dramatic intonation have been told that the pyramids were built from millions of limestone blocks hauled into place by teams of workers, ramps, sledges, levers, and sheer stubbornness.

But the new hypothesis suggests this narrative may have been a misunderstanding caused by a mistranslation of an ancient inscription. Where scholars previously read “We built the great house of eternity,” Dr. El-Mostafa’s team now suggests the original hieroglyphs more accurately mean “We made the rock less rock-like until it resembled a triangle.”

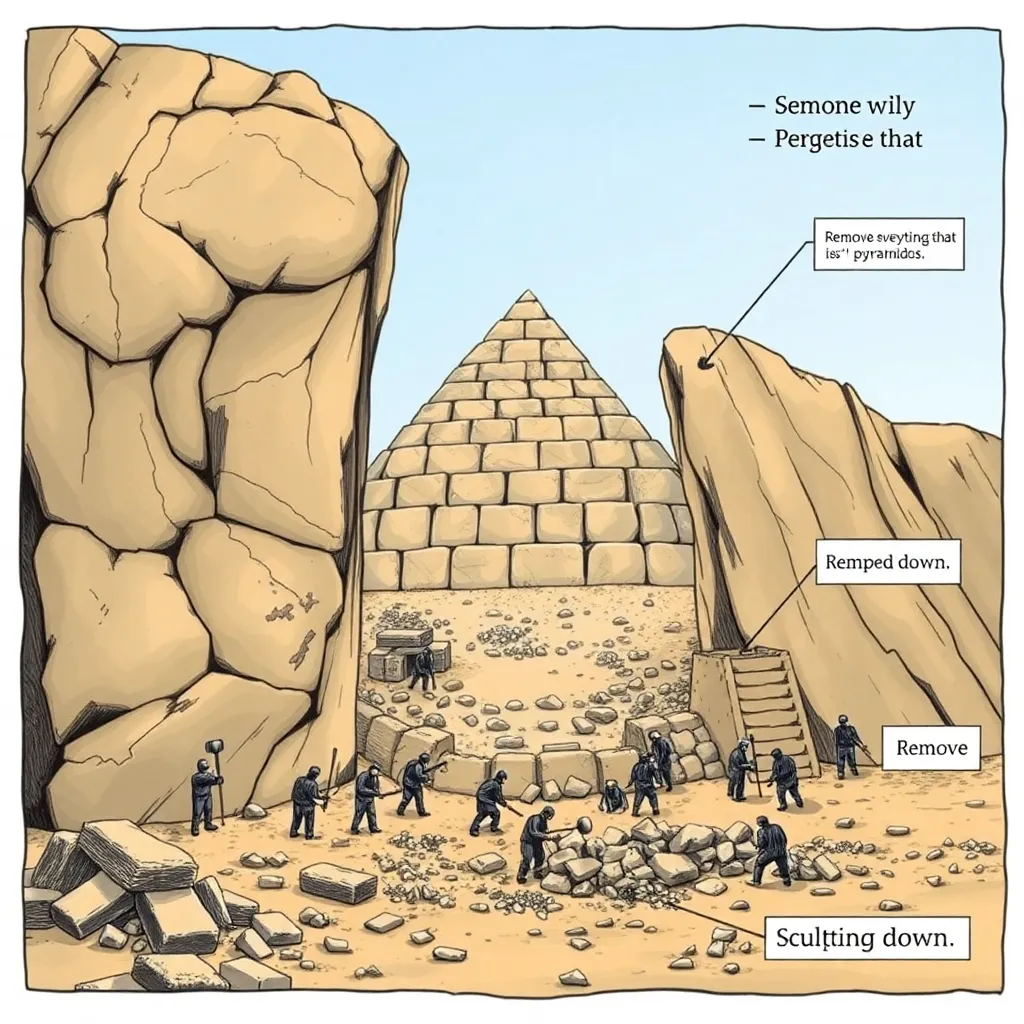

Under the “reverse-building” model, builders began with a single, enormous plateau-sized rock and simply carved away everything that did not look like a pyramid. The scraps were then processed into a fine powder and distributed artistically across North Africa to create the world’s most famous sand-themed region.

“It’s the most elegant system imaginable,” said Dr. El-Mostafa. “No transportation costs, no complicated supply chain. Just continuous chiseling and a national sand plan.”

Sand: Not a Natural Feature, But a Byproduct

The most controversial component of the theory is the claim that the Sahara Desert—often viewed as a naturally occurring expanse shaped by climate and wind—may, in fact, be largely industrial waste from pyramid production.

“This is what’s so exciting,” said study co-author Professor Martin Hedges of the University of East Wessex. “We’ve been treating sand like it’s just sand. But what if it’s actually the ancient equivalent of sawdust from a very large carpentry project?”

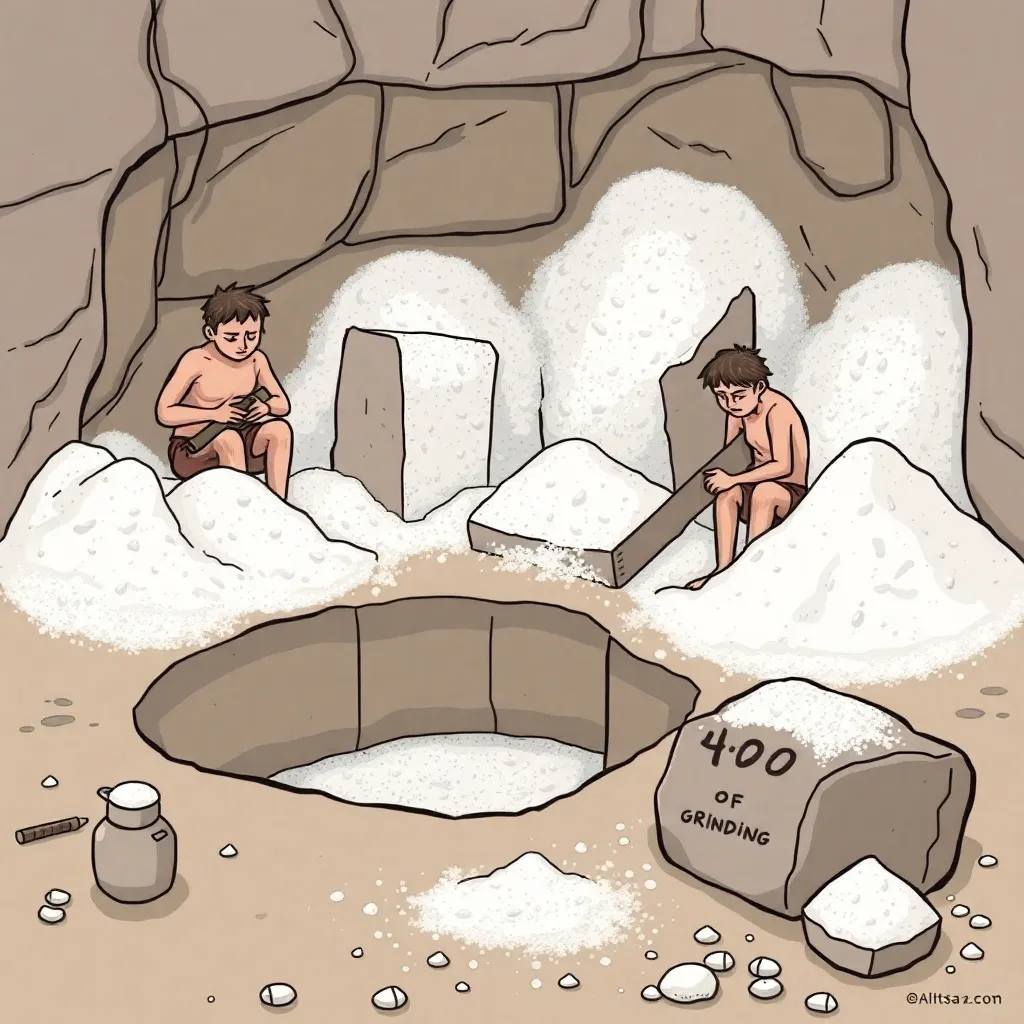

According to the paper, Egyptian laborers developed early grinding techniques, including:

Hand-querns the size of small courtyards, operated by rotating teams and existential dread.

Stone-on-stone abrasion pits, in which surplus limestone was rubbed against other surplus limestone until both became morale problems.

A ceremonial “Sand Festival,” during which nobles gathered to watch the final grinding phase and applaud politely while someone nearby calculated the remaining 400 years of grinding.

The researchers estimate that a single pyramid could produce enough sand to fill “several deserts,” depending on the ambition of the pharaoh and whether or not the workforce was allowed weekends.

Evidence Includes “Suspiciously Convenient Rock Vibes”

While skeptics have noted the relative absence of “one big rock shaped like a pyramid with a pyramid inside it” in the archaeological record, proponents insist there are subtle clues.

“These pyramids have corners that look like they’ve been carved,” said Hedges. “Which is a major red flag, because a structure built from blocks would obviously have… corners too. But different corners.”

The team also points to the “bedrock adjacency phenomenon,” in which many pyramids sit on rock.

“People are like, ‘Of course they sit on rock, everything sits on rock,’” Hedges said. “That’s exactly the kind of incurious thinking that has held this field back.”

Other alleged indicators include:

Tool marks that could be interpreted as either ancient carving or, as skeptics argue, “exactly what you’d expect when you cut stones to fit.”

A newly analyzed grain of sand that, under magnification, looked “slightly limestone-ish.”

A papyrus fragment reading: “Reminder: grind the leftovers. The king hates clutter.”

The Ramp Lobby Furious

Predictably, the announcement has enraged supporters of the traditional “ramp theory,” who have spent decades constructing scale models, building experimental sledges, and filming earnest television specials in which someone in a linen tunic shouts, “Heave!”

“This is an attack on our entire community,” said prominent ramp theorist and part-time reenactor Gerald N. Pritchard. “If they weren’t using ramps, then why have I been building ramps in my backyard for twenty years? What am I supposed to do with my ramp collection?”

Pritchard also questioned the logistical plausibility of grinding down that much stone into sand.

“Do they have any idea how long that would take?” he demanded. “You’d need thousands of workers, years of organization, and a society capable of sustained, coordinated labor—exactly the kind of society that could also, incidentally, move blocks up ramps.”

At press time, Pritchard had begun publishing an alternative compromise theory: that the pyramids were carved from bedrock, but the sand was still delivered via ramps “on principle.”

Tourism Industry Already Pivoting

Egypt’s tourism sector has responded swiftly, unveiling a new marketing slogan: “Come See What We Removed.”

Tour guides have begun adjusting their scripts accordingly.

“On your left, you will see the Great Pyramid,” said one guide near Giza. “On your right, you will see the missing parts of the Great Pyramid, which we have thoughtfully spread over a continent for your convenience.”

Souvenir shops are reportedly preparing new product lines, including:

“Authentic Pyramid Excess” jars of sand

Miniature chisels labeled “Official Reverse-Builder Tool”

T-shirts reading: I VISITED THE PYRAMIDS AND ALL I GOT WAS THIS ENTIRE DESERT

One luxury tour company is advertising a premium package in which guests are taken to an undisclosed dune and told, “This was definitely part of Khufu.”

Experts Warn of Dangerous Precedent for Modern Construction

Architects and engineers have expressed concern that the theory could inspire a trend in contemporary building projects: simply carving skyscrapers out of mountains and declaring the debris “art.”

“We’re already struggling to keep clients from asking if their new kitchen can be ‘hewn from the living granite of destiny,’” said London architect Priya Malhotra. “This isn’t helping.”

A spokesperson for a major construction firm confirmed that several CEOs have become “visibly excited” by the idea of billing a project as both demolition and construction simultaneously.

“It’s the same work twice,” the spokesperson said, “but now it’s aspirational.”

What Happens Next: The Search for the “Original Mega-Rock”

The research team’s next step is to locate the theoretical “proto-pyramid bedrock mass” from which the pyramids were carved. When asked what this would look like, Dr. El-Mostafa replied, “A smaller amount of rock than you’d expect, plus a lot of sand.”

Critics argue that this description could apply to most places on Earth.

Undeterred, the team has already proposed further applications of the reverse-building framework, including the possibility that:

The Sphinx was carved out of an even bigger lion, and the rest was distributed as gravel.

Ancient obelisks were “un-carved” from the sky, explaining clouds.

Cleopatra didn’t wear eyeliner; the Nile just had “very strong vibes.”

A Nation Divided, But Mostly Just Confused

Public response in Egypt has been mixed. Some residents welcomed the idea as a testament to ancient ingenuity. Others questioned why anyone would take a perfectly good plateau and turn it into a triangle, only to spend centuries cleaning up the mess.

“Do you know how hard it is to get sand out of things?” asked Cairo local Mahmoud El-Sayed. “If they invented the pyramid by creating sand, then they also invented the problem of sand.”

For now, archaeologists remain cautious, pointing out that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, and also a convincing explanation for why ancient Egyptians would choose the most labor-intensive method possible for generating both a monument and a continent-spanning nuisance.

Still, Dr. El-Mostafa remains optimistic.

“In every era, humanity asks the same question,” she said. “Did our ancestors move heavy blocks with ramps, teamwork, and planning… or did they spend their lives grinding a mountain into dust?”

She paused, looking out over the desert as the wind lifted a thin veil of sand into the air.

“The answer,” she said, “has been blowing in our faces this whole time.”